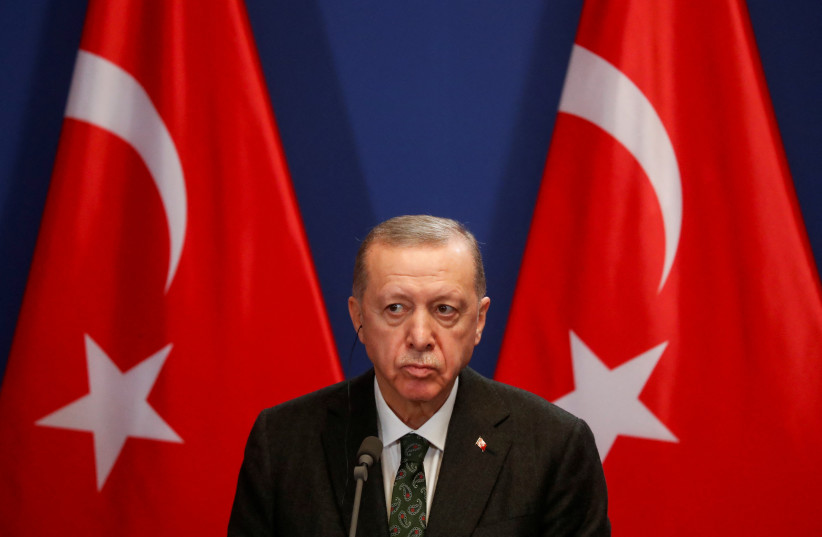

Behind The Lines: The Turkish leader sounds like, and acts like, an enemy of Israel. It is overdue that he be properly recognized as one.

By JONATHAN SPYERAUGUST 2, 2024 20:15

https://trinitymedia.ai/player/trinity-player.php?language=en&pageURL=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.jpost.com%2Fmiddle-east%2Farticle-812988%23812988&unitId=2900003088&userId=a6891305-3a80-42c0-a0e7-fa277fabb1c1&isLegacyBrowser=false&isPartitioningSupport=1&version=20240801_6cb27f0350dcc59d21847568158c07b16c29d9b4&useBunnyCDN=0&themeId=140&unitType=tts-player

On July 28, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan appeared to threaten violence against Israel. Speaking in his hometown of Rize, Erdogan said, “We must be very strong so that Israel can’t do these ridiculous things to Palestine. Just like we entered Karabakh, just like we entered Libya, we might do similarly to them.”

Erdogan’s comments were widely reported. Reuters noted, however, that the Turkish president “did not spell out what sort of intervention he was suggesting.” It is true that the Islamist Turkish leader did not go into specifics. Nevertheless, his quoted statements do offer a clue as to what he was referring to, which deserves closer attention.

Erdogan’s choice of examples should be carefully noted. Turkey, after all, has conducted many military interventions in recent history.

Just a half century ago this year, Turkish airborne forces carried out a swift invasion of Cyprus. At the present time, Turkish troops are engaged in an open-ended incursion in Iraq, against the insurgent Kurdish Workers Party (PKK).

The Turkish president chose not, however, to refer to either of these feats of Turkish arms. Instead, he mentioned two lesser recent interventions – into Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh.

It can be assumed that he did not choose these examples randomly. It is hence worth taking a look at the form of Ankara’s intervention into these conflicts, in order to be aware of what the Turkish president may be hoping to cook up for Israel.

The Turkish interventions into Libya and Karabakh, unlike those into Cyprus and Iraq, were chiefly characterized by the major role played by non-state bodies and proxy fighters.

In 2020, I carried out an in-depth study of Turkey’s Libya and Karabakh interventions, in cooperation with my colleague, Turkish-born Hay Eytan Cohen Yanarocak. We noted that in both cases, the recruitment and deployment of proxy fighters was managed by the Turkish private security firm SADAT, under contract from the Turkish government.

The SADAT International Defense Consulting Company was established in 2012 as the only privately owned defense consulting firm in Turkey. The company was founded by Brig.-Gen. (res.) Adnan Tanriverdi and 22 comrades in arms who all were expelled from the Turkish Armed Forces because of their support for political Islam. Melih Tanriverdi, son of Adnan, is the current CEO of the group.

A strong relationship to fuel the flames

The elder Tanriverdi and Erdogan have known each other since 1994 when both served in Istanbul, Erdogan as mayor and Tanriverdi as commander of Maltepe military base in the city. The two leaders forged a strong relationship. Following the failed coup attempt in July 2016, Tanriverdi was nominated as Erdogan’s top military adviser.

He then led a comprehensive overhaul of the army. He shut down the military academies, which were strongholds of Turkish secularism, and replaced them with a National Defense University. This latter institution recruited students from the religious Imam Hatip schools.

On January 8, 2020, Tanriverdi had to resign because of a controversial speech at the third International Islamic Union Congress in December 2019.

In Libya, SADAT recruited from among Syrian rebel fighters aligned with Turkey, and was responsible for their recruitment, travel, and deployment to Libya in defense of the Muslim Brotherhood-associated Government of National Accord of Fayez al-Sarraj.

On the ground in the country, SADAT worked in close cooperation with a Palestinian Islamist, Fawzi Boukatif, in the deployment of the Syrian fighters.

According to a report by the US military’s Africa Command, presented to the US Office of the Inspector-General on August 28, 2020, approximately 5,000 Syrians fought with the GNA in Libya. The report, according to Jane’s Information Group, noted that “Syrians fighting for the GNA are paid and supervised by ‘several dozen’ military trainers from a Turkish company called Sadat, which also trains GNA-aligned militias.”

These fighters played a significant role in the Sarraj government’s successful expulsion of Gen. Khalifa Haftar’s forces from the entirety of the Tripoli area.

In Nagorno-Karabakh, similarly, Syrian fighters were recruited and deployed by SADAT, in cooperation with the official Turkish Armed Forces.

The fighters were offered monthly fees of $1,500-2,000 for agreeing to serve in the southern Caucasus. The contracts were for three to six months. The main recruitment centers were in the cities of Afrin, al-Bab, Ras al-Ain, and Tel Abyad. Fighters crossed the border at Kilis and were then transported to the Gaziantep Airport. From there, SADAT-chartered A-400 transport aircraft and flew them to Istanbul Airport, and from there they boarded flights to Baku, Azerbaijan.

Sadat is unlikely to be chartering aircraft and funneling fighters to the Gaza Strip or West Bank anytime soon. But the model according to which the Turkish state cooperates and contracts with ostensibly private Islamist bodies in order to pursue goals that go beyond Ankara’s official diplomatic goals and relationships is worthy of close scrutiny.

SADAT, indeed, takes a close interest in Israel. Tanriverdi, in a 2019 speech translated by the Middle East Media Research Institute, said that “the Islamic world should prepare an army for Palestine from outside Palestine. Israel should know that if it bombs [Palestine], a bomb will fall on Tel Aviv as well.”

The interest appears to be more than merely rhetorical. In 2018, the Shin Bet (Israel Security Agency) accused the organization of transferring funds to Hamas. A Turkish academic, Cemil Tekeli, was arrested by Israeli security officers and accused of money laundering. Later, Tekeli’s picture with Tanriverdi also surfaced in the Makor Rishon newspaper.

Following the October 7 attacks, a think tank maintained by SADAT issued a statement in support of Hamas’s actions. The statement proposed the formation and deployment of an “Islamic army” to end Israel’s “occupation.”

So Erdogan’s listeners would have understood well what their president was referring to in his remarks. The Turkish leader was hinting that the methods of proxy warfare which have characterized Turkish activity in the region over the last decade might be applied also to the Israeli-Palestinian context.

Erdogan is known for his rhetorical verbosity and extravagance. In this case, however, it would be a mistake to dismiss the statement as mere hot air.

Turkey’s continued domiciling of an active Hamas office and its provision of passports to Hamas operatives are a matter of public record.

In July 2023, Israeli customs authorities intercepted 16 tons of explosive material on its way from Turkey to Gaza, disguised as building material. Thus, Erdogan and Turkey’s support for Hamas is already far beyond the realm of rhetoric.

A close watch on Turkey’s proxy war activities, and in particular on the role of SADAT, is in order.

The Turkish leader sounds like, and acts like, an enemy of Israel. It is overdue that he be properly recognized as one.